Heritage copywriting for Knole, a National Trust property

Breathing space for our 200-year-old sycamore

Our elderly sycamore needs more air. Too little oxygen was getting to the roots because the ground above had become compacted. So we’ve loosened the soil to let in the air, and added a fence to protect it from hooves and feet.

Trees for a grand landscape

Sycamores became popular landscape trees during the 17th century. This is one of a pair that were planted around 1800, possibly to replace earlier ones that had died.

Sycamores can live for over 400 years, but that’s unusual. 250 years is more common. With luck and light soils, our sycamore will breathe good Kent air for another 50 years or so.

Our thanks go to Tate Fencing who installed the fence and contributed to the cost of this project.

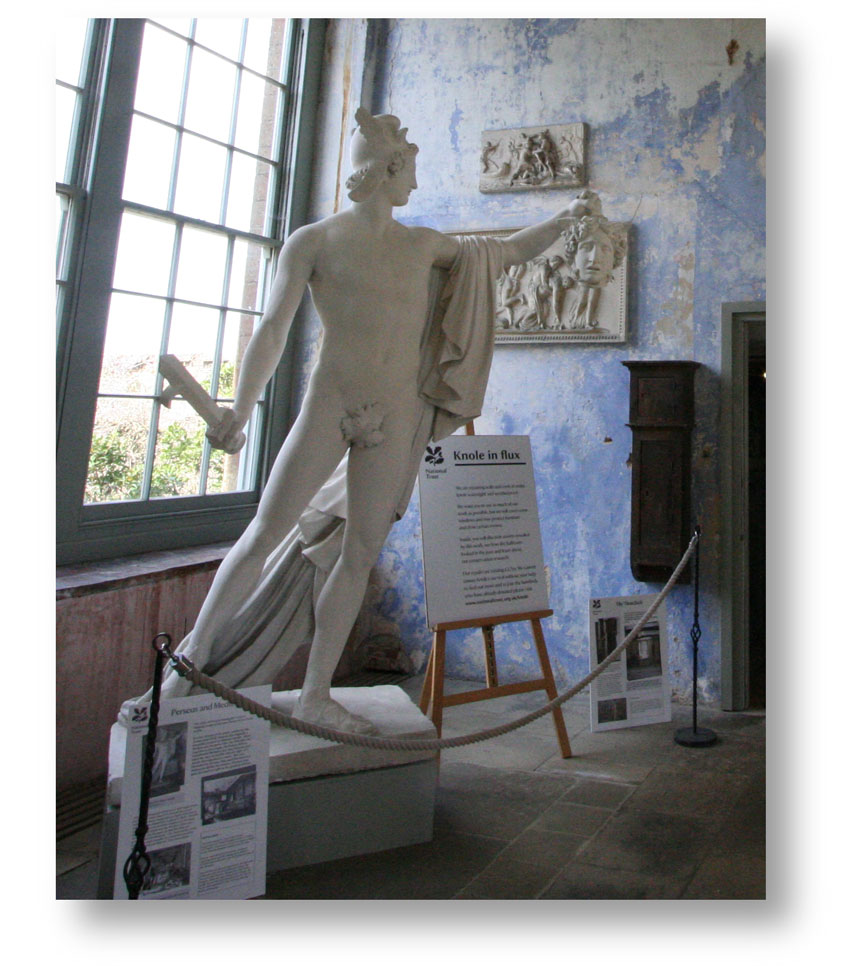

A fashionable reproduction

The plaster statue of Perseus holding Medusa’s head is a copy of a statue carved between 1800 and 1801 by Venetian sculptor, Antonio Canova (1757–1822). The original is in the Vatican. Our copy was probably made for John Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset. We don’t know who cast it.

Been there, bought the statue

Copies of famous statues were popular among the aristocracy. Many wealthy men – including John Sackville – would have seen the originals when they worked their way round the great sights of Europe on the Grand Tour, a near-obligatory cultural trip for aristocratic young gentlemen.

A photograph from 1881 shows the statue in the Great Hall. It was still there in a 1906 photograph. By 1911 it had gone; it was probably here in the Orangery.

The face of rage

Medusa was a beautiful priestess in the temple of Athena. When she made love in the temple to the sea god, Poseidon, Athena turned Medusa’s hair into serpents and made her face so terrible to behold, it turned onlookers to stone.

Medusa was later beheaded by Perseus who used her head as a weapon to defeat his enemies. The statue shows Perseus with sword and severed head. Its title, Perseus Triumphant, captures that moment of victory.

After years of neglect, a five-year programme of repairs and conservation opened up new rooms and welcomed new audiences. My job as a heritage copywriter was to capture the essence of this townlike building – to help non-specialists make sense of it. I wrote a communication guide for the Knole team and much of the signage for the new visitor centre.